Listen Here on The Web

Or on your favorite podcast app below:

Or Watch Here on YouTube

Transcript:

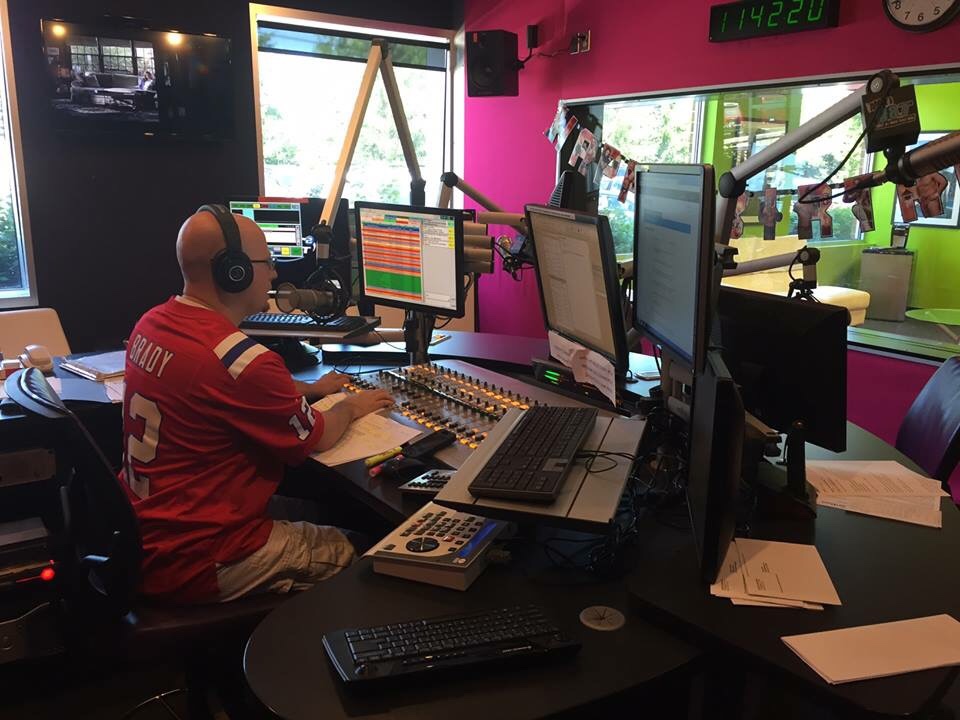

Welcome in, I'm Jon Gay. As you hear in my intro, I'm a radio guy turned podcaster. And if you're watching this on video, you can see I'm wearing my old fleece from Detroit's 98.7 Amp Radio, the last radio job I had. It no longer exists, much like 3 1/2 of the 5 music stations I worked for full time since 2004. (The half is 95 Triple X in Vermont that only has live DJ's for parts of weekdays.)

When in radio, I rolled eyes at those "bitter old radio guys" who said "back in my day." This is not me being bitter about being out of radio. Professionally, I'm really happy. But what upsets me is what's happened to an industry that I loved. I wanna be clear - this is NOT an indictment of the many people who work hard in the trenches every day and get paid way less than their worth, and try to bring you compelling content 24x7, now with smaller staffs than ever. Many of those people are my friends - and hopefully still will be by the time I finish this.

Radio has been around for over 100 years, and traditionally, rumors of its demise have been greatly exaggerated. TV was going to make it obsolete. Then the World Wide Web was going to. But music radio beat back all challengers and stayed relevant - thanks to two key ingredients - music and personality. And I think as an industry, we felt invincible. But there's been a perfect storm of threats to music radio over the last 25 years.

I promise this isn't going to be a history class, but this piece is where it all starts. A quarter century ago, Congress and President Clinton passed and signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Prior to this, there were strict caps on how many radio stations one company could own - as well as how many media outlets in general. This new law relaxed those caps, with the idea that it would foster greater competition. But there was an unintended side effect.

With the economy booming in the late 90s, some companies went on a spending spree - most notably the Mays family, who made their money on oil in San Antonio, and owned a couple radio stations there. The Mays family's company, ClearChannel, bought everything they could get their hands on, at one point owning over 1,100 radio stations across the country, everywhere from large markets to small. Seemed like a solid investment - until the economic downturn in the early 2000's. Now, the company (and others) were saddled with theses assets (radio stations) that they overpaid for, and they were losing money. The company was now publicly traded, and it had stockholders to answer to. So they started making widespread cuts, before eventually taking a leveraged buyout. And they pioneered the practice of voicetracking - which allowed DJ's to pre-record shows - first their own, then over a network to other cities, in place of other paid employees. Thus, in a cost-cutting move, the product started to get watered down, losing its unique selling proposition - its personality.

Budget cuts continued through the decade - I was laid off from ClearChannel Burlington, Vermont, in December of 2006, shortly before they sold off the small market stations to another owner. Their biggest single day of layoffs was January 20, 2009. When you think about it, it was a savvy PR move - the news would get buried under the inauguration of America's first Black President. Across the country, other large radio companies were facing similar challenges.

Also around this time, ratings technology changed. Previously, participating listeners would fill out ratings diaries, jotting down which stations they listened to and for how long. This of course, allowed for high human error. You didn't need to get someone to listen to your station - you just had to get them to "think" they did when they filled out the diary. Also, the way most of us punch around our presets in the car, a diary won't reflect that.

So Arbitron, now Nielsen, the ratings company, invented the PPM - or portable people meter. Respondents would carry them around, like a pager or cell phone, and it would record what stations the user was listening to. There were issues with headphones, and small sample sizes, but it seemed more accurate than the old system. PPM's were used in most of the 50 largest cities in the country, but then some problems cropped up.

An hour is divided into 4 equal quarter-hours. Think of a clock, cut in fourths. There's 00-15, 15-30, 30-45, and 45-00. In order to get credit for a "quarter hour" of a listener, you had to get 5 full minutes out of that 15 minute window. It could be all at once, in 5 one-minute increments, or any other combo. But you needed 5 full minutes. So, to maximize the opportunity to claim listeners, radio stations had to spread their increasingly long commercial breaks across TWO quarter hours. So they'd straddle either 00, 15, 30, or 45. And EVERY station did this. Have you ever been in the car and gotten frustrated that everyone's on commercials at the same time? Next time that happens, look at the clock. I'll almost guarantee it's right around a quarter hour. And now, if you're in the car, it's easier than ever to switch to Sirius, Spotify, Pandora, etc and never come back. More on that in a moment.

The other problem with Portable People Meters is that it accurately showed tune-out when music DJ's talked too long. So they told us, make it all about the music, and talk less. In a massive overreaction, one company even told its music DJ's to limit all of their talk breaks to 7 seconds or less. This further eliminated radio's personality. What these short-sighted bean counters did not account for, is that if a DJ is compelling, people will listen. Now, I'm not going to tell you that I was the world's greatest DJ, far from it. But I was good enough to work in a large market like Detroit twice, and run a station in New Orleans. When I was doing nights here on Channel 955, we looked at the ratings. We'd have meters during the song, keep them during the minute or so of a phone topic I did, and many would even stay through the station promo, if it was compelling. They didn't drop off until the commercials started. So rather than working with DJ's to make sure we had compelling content, they muzzled us in favor of the music.

This might have worked, except that Spotify, Pandora, and other all music services were starting to come into their own. Sure, in 2000, the idea that music radio stations should be all about the music might have worked. But by 2011, with the accessibility of these apps, why would you expect a listener to spend time with a radio programmer's playlist, when they could easily make their own? So first, music radio eliminated its personality, then they lost their other key selling point - being the go-to for music.

Now, I'm not saying all radio is dead. News, sports, talk, and morning shows on music stations are all still holding their own. Why? Personality. Of the 5 music radio stations I worked for full time since 2004, the only one that still exists in the same form is Channel 955 here in Detroit. Why? Their morning show host, Mojo in the Morning, is a bigger brand and has been around longer than the station itself. It's a personality driven morning show that has unique content consumers can't find anywhere else.

Ok, why have I chosen this week to talk about the death of music radio? Because it's no longer pundits like me who are saying this. The actions of the two largest radio operators in the country prove they agree.

ClearChannel rebranded itself as iHeartMedia in 2014, in an effort to shed the negative connotations around their old name. A few years later, they filed bankruptcy due to its $20+ billion debt. At any rate, they've been focused on podcasts, in person events, and other aspects of entertainment. And just over a month ago, they announced a new organizational structure. There will be two divisions. The Digital Audio Group will focus on all things digital, including the many companies they've bought as they continued to lay off their radio employees. The other side, the Multiplatform group, will focus on live and virtual events, digital sales, data targeting, and, oh by the way, it's 800+ radio stations. Missing from the name of both groups: the word radio. Resources continue to be diverted from traditional radio to digital.

The second largest owner is the company formerly known as Entercom, which bought CBS Radio in 2017. Entercom, short for entertainment communications, had operated mainly in medium sized markets, then they acquired the large market, high profile assets of CBS. They scrambled to emulate iHeart's infrastructure for streamlining costs. In 2020, they began consolidating DJ's ala iHeart, having a handful of DJ's voice shows for similarly formatted stations all over the country. And like their competitors, they continued investing in digital while cutting on the music radio side.

Then, this week, in a spectacularly face-palm move, the company announced a full rebrand. Entercom would now be know as "Audacy." That's A-U-D-A-C-Y. It's supposed to be a clever combination of the words, audio, audacity, and odyssey. But anyone who sees the name is going to see the word "Audacity," which, coincidentally, is the name of a free-ware audio editing program that I despise. Anywho, Audacy is going to focus on live events, podcasting, on-demand audio, and even has a partnership with the Bet MGM sports gambling app. They even sent out a tweet promoting six of their heritage brand radio stations. Two of the six, LA's K-ROCK and Chicago's B96, are struggling in recent ratings. And another, Boston's 50-year Heritage rock station WAAF, was sold to a Christian broadcasting company just over a year ago. Talk about the left hand not talking to the right hand. Here's the tweet:

https://twitter.com/Audacy/status/1376987662565933061?s=20

But here's the biggest jaw-dropper. Ever heard of the radio dot com app? That was CBS, then Entercom. Audacy is going to "sunset" both the app, and the domain radio dot com as part of the rebrand. As my colleague Matt Cundill points out, radio has become a four letter word. How much would the domain "radio dot com" have been worth 10 years ago? Now, Entercom...excuse me, Audacy...is basically throwing it away. The two biggest players in commercial radio don't even want to be associated with the word radio anymore.

I'm not ready to pull the plug on music radio just yet. And there are some diamond-in-the-rough stations across this country that still connect with their listeners. But if radio is going to get off life support, smaller local companies need to buy radio stations back from these corporate behemouths. Programming decisions need to be made by radio people, not CPA's. Why are podcasts so big now, with over 2 million in existence? Because people want to connect with other people - that's never been more true than in the pandemic.

Look, AM and FM radio transmitters may become relics of the past, as 4G, 5G, and more proliferate our world. What used to be an "over the air" broadcast may become completely digital and online. But whatever the delivery method, the product matters. And with the big boys abandoning local radio for podcasts and more, it's going to take a revolution to bring radio back. And for those of you in it, keep fighting the good fight.